Who Is...Paschal?

Nov 28

Every now and then, LRL patrons will ask a question like, "who is Vernon and why is his name on the Texas statutes?" To which we say, "good question!" People often conduct legislative history research with a tight deadline that doesn't leave much time for musing over the origins of the sources, but it can be instructive to learn about who has worked to compile Texas' laws over the years. In our occasional "Who Is…" series, we'll take a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the publishers, lawyers, and legal scholars behind them. Check out our previous entries on Vernon and Sayles; in this post, we're focusing on George W. Paschal.

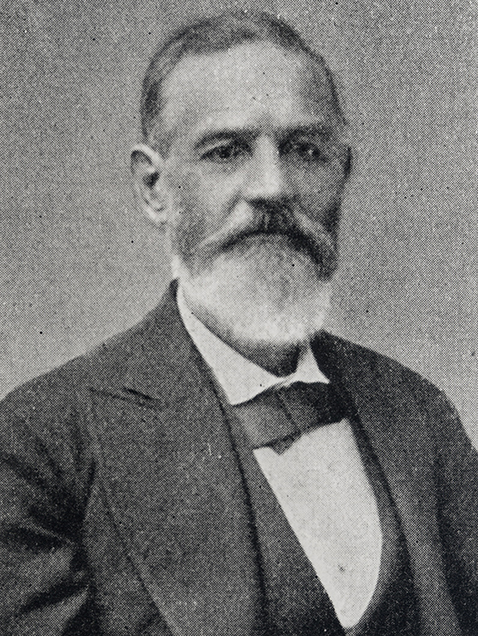

From Arkansas Supreme Court justice to newspaper editor, lawyer to court reporter, George W. Paschal wore many hats over his life and never seemed to follow the crowd—in fact, one could argue he relished the path of most resistance. He is responsible for the most successful of the early compilations of Texas statutes, A Digest of the Laws of Texas (commonly referred to as Paschal's Digest).

Born in Skull Shoals in Greene County, Georgia, in 1812, Paschal worked his way through the State Academy in Athens, Ga., by teaching and keeping books.[1] He was admitted to the Georgia Bar before he turned 20 in 1832. He practiced law in Georgia for four years before receiving orders to serve as the aide-de-camp to General John E. Wool with the Georgia Militia, which had been charged with suppressing a Cherokee uprising. Here we get one of our first hints of Paschal's unconventional ways: he married the daughter of one of the Cherokee chiefs, Sarah Ridge. That military campaign led to the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, and ultimately to what we know today as the Trail of Tears.[2]

The couple moved to Arkansas in 1837 to be closer to Sarah's now-relocated family. Paschal began his law practice in Benton County, where he sometimes jointly represented clients with Royal T. Wheeler (future chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court). Sadly, Sarah’s father, brother, and cousin were assassinated in 1839 by Cherokees who were angry about the family’s support of the Treaty of New Echota. The Paschals chose to remain in Arkansas, and in 1843, the Arkansas Legislature selected George as an associate justice on the state’s Supreme Court.[3]

However, he served just one term on the court, then resigned in August 1843 so he could represent the Cherokees in claims against the United States.[4] A victory in that case led to ratification of the Treaty with the Cherokee in 1846, which awarded reparations to the Cherokee.[5]

George and Sarah then moved to Texas around 1846, and George was admitted to the Texas Bar in December 1847. In 1850, Sarah began treating Galvestonians suffering from yellow fever in their home. The couple divorced later that year.[6]

George moved to Austin and remarried (Marcia Duval Price), practiced law, and began work in 1856 as editor of the Southern Intelligencer, an antisecessionist, pro-Union publication. The paper quickly developed a rivalry with the Texas State Gazette, which promoted states’ rights and reopening the slave trade in Texas. The rivalry went as far as a duel challenge, and Paschal resigned his post in 1860.[7] It should be noted that although Paschal was against reopening the slave trade, he also was against abolition and was himself a slave holder.[8]

Paschal further acted on his Unionist principles by representing a captured Confederate conscript, F.H. Coupland, in 1862. He obtained a writ of habeas corpus from his old friend (now Texas Supreme Court Justice) Wheeler, but before it could be served, Coupland was drafted into the army, and Paschal was arrested and jailed for a short time by Confederate authorities.[9]

Indeed, times were tough for a Unionist lawyer in Texas during the Civil War, so Paschal committed himself to preparing the Digest of the Laws of Texas. He writes about this decision in the preface to the Digest’s first edition “…differing as the editor did with the majority of the people of his state, as to the right of secession, and the necessities of the measure, as well as to the possibility of success, and not wishing to seek a professional field elsewhere, had that been possible, he thought that he could not more usefully employ his time than to give those years to the preparation of a book, which should answer the double object of presenting the Statutes, and a pretty full Digest of the decisions of the Supreme Court, in the same volume.”[10]

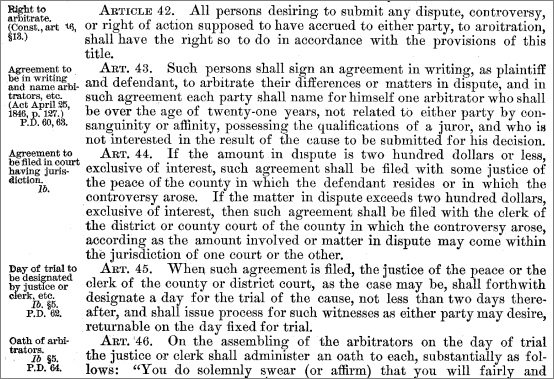

Paschal’s Digest offered a few things not seen in previous legislative publications. Current statutes can trace their history to the sections in his Digest—previously, statutes had been arranged chronologically.[11] Additionally, his statutes presented “the old law, the mischief and the remedy, in the same view”—meaning, he printed the current law alongside the repealed law or judicial changes, using different typefaces to illustrate the development of the law.[12] Finally, and most significantly, “…his digest of laws appeared in five editions, the last one being the basis for the first official compilation of statutes in 1879. Many articles in the [1925] statutes retain not only the substance but also the verbatim phrasing of Paschal’s sections.”[13] (See image of Articles 42-46 from the 1879 Revised Civil Statutes, which includes marginal notes crediting where language was taken from P.D.—Paschal's Digest.)

After the war, Paschal was appointed by provisional governor Andrew Jackson Hamilton as Texas’ agent in a case concerning the Confederacy’s attempts to redeem U.S.-issued bonds to help pay for the Confederate war effort. He ultimately argued before the U.S. Supreme Court and won, helping to provide the definitive ruling on the constitutionality of secession. Paschal also served as counsel in the “Emancipation Cases” to determine on what date enslaved peoples officially gained their freedom in Texas. (The majority ruling settled on the date of ratification of the 13th Amendment.)[14]

In 1868—about the same time that the constitutionally illegitimate Military Court began—Paschal was appointed as court reporter. Drummond observes that “Paschal's reports are characterized by his sometimes polarizing, always frank, and consistently entertaining (and subsequently essential) historical asides contained in the prefaces to each [Texas Reports] volume.” He additionally used the Texas Reports to advertise his other publications. Paschal’s signature candor likely contributed to him losing this job, as he published in Texas Reports his negative commentary on changes to court reporter guidelines.[15]

Paschal then moved to Washington, D.C., where he opened a law office with his sons, George Jr. and Ridge. He also married his third wife, Mary Scoville Harper, and lectured at the Georgetown University law school. He died in Washington in 1878.[16]

In addition to his work with Texas laws, George W. Paschal found himself at the crossroads of many historical events. And as a man dedicated to the law, the defense of them seemed to guide his principles: “Human rights are of all sciences those which most affect human happiness. They can only be preserved by the eternal vigilance of the masses. That vigilance should constantly be directed to our laws, organic or statute. It is under the forms of these that liberty is preserved or lost.”[17]

Photograph of George W. Paschal courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Title page of Paschal's Digest taken from the LRL's digitized 5th edition. Excerpt of Title VI, Articles 42-46 from the 1879 Revised Civil Statutes, courtesy of the Texas State Law Library's Historical Texas Statutes digital collection.

[1] Amelia W. Williams, "Paschal, George Washington," Handbook of Texas Online, accessed August 29, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpa46.

[2] Dylan O. Drummond, "George W. Paschal: Justice, Court Reporter, and Iconoclast," Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society 2:4 (Summer 2013), accessed 2017 October 17, http://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/george-w-paschal-justice-court-report-22105/, p. 7.

[3] Drummond, p. 8.

[4] Drummond, p. 8.

[5] Treaty with the Cherokee, 9 Stat. 871, 874 (1846)

[6] Drummond, p. 8.

[7] Williams; Drummond, p.8.

[8] Williams; Kevin Ladd, “Pix, Sarah Ridge,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 15, 2017, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpi30; Fannie E. Rachford, “O’Connor, Elizabeth Paschal,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 15, 2017, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/foc12.

[9] Drummond, p. 8.

[10] "Preface [to the first edition, 1866], " A Digest of the Laws of Texas, 5th edition, edited by George W. Paschal. Houston, TX: E.H. Cushing, 1878, p. iv, http://www.lrl.texas.gov/collections/Paschal.cfm.

[11] "Legislation," rev. by Linda Gardner, A Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History, edited by Karl T. Gruben and James E. Hambleton, Austin, TX: Butterworth Legal Publishers, 1987, pp. 16-17.

[12] "Preface [to the first edition, 1866], " p. iv.

[13] Marian Boner, "The Attorney as Author: Books Written and Used by Texas Lawyers, " Centennial History of the Texas Bar, 1882—1982. Austin, TX: The Committee on History and Tradition of the State Bar of Texas, 1981, p. 145.

[14] Drummond, pp. 9-10.

[15] Drummond, p. 11.

[16] Williams.

[17] "Preface to the fourth edition [1874], " A Digest of the Laws of Texas, 5th edition, edited by George W. Paschal. Houston, TX: E.H. Cushing, 1878, pp. xi-xii, http://www.lrl.texas.gov/collections/Paschal.cfm.