In 2015, Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller announced that the boll weevil had been completely eradicated in the West Texas Maintenance Area, and that it was functionally eradicated in several other regions. Around a hundred years after the cotton crop pest was first noted to be in Texas, the bugs are finally, mostly, gone...or at least more controlled.

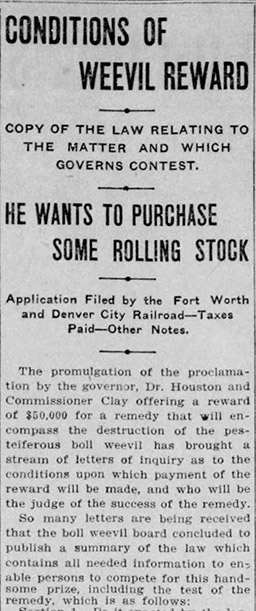

But in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the snout beetle's destructive impact on the Texas cotton industry was looking quite dire. Described in the Handbook of Texas Online as "one of the most devastating pests ever introduced to American agriculture," an estimated 700,000 bales were lost to the boll weevil in 1904, at a cost of $42 million. The blow to Texas' cotton culture kept growing as the insects spread to every cotton production area in Texas. Boll weevils resisted all of the agriculture industry's conventional insecticides and anti-pest practices of the time.

Something had to be done. In 1899, the state appointed Frederick W. Mally as state entomologist and charged him with combating the weevils. His plans were lauded by subsequent entomologists, but heavy rainfall and the Galveston hurricane of 1900, along with inadequate funding, derailed his efforts.

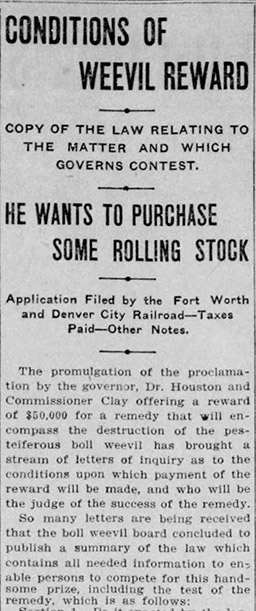

E. Dwight Sanderson was named the next state entomologist in 1901. The state also decided to try a new tactic. With HB 243, 28R, the legislature appropriated a $50,000 prize "to be paid to any one who will discover and furnish a practical remedy that will exterminate the cotton boll weevil, and $2,500.00 for expenses and per diem of committee to pass on the findings of said person or persons." In today's dollars, that prize would be more than $1 million—but still just a fraction of the money that was lost annually to the boll weevil's destruction. Gov. S.W.T. Lanham announced the award 115 years ago this week, on the steps of the Capitol in July 1903.

According to the Handbook of Texas, "the prize offered by the legislature made both themselves and the boll weevil a figure of fun for newspapers throughout the nation, and this episode is sometimes found in civics or government texts as an illustration of the foolishness of lawmaking bodies." Although Texas newspaper articles testify to citizens' interest in the prize, it was never claimed.

Between 1899 and 2013, 32 bills were introduced with "boll weevil" in the caption, illustrating the ongoing battle with the bugs. The current statutes on "Cotton Diseases and Pests" can be found in Chapter 74 of the Agriculture Code. Starting around 1903, boll weevil pest management efforts began to see more promising results on Walter C. Porter's demonstration farm at Terrell, under the leadership of Seaman A. Knapp. Most recently, with the help of the Texas Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation (established by SB 30, 73R), boll weevils are much fewer and farther between in Texas now…without the incentive of cash prizes from the Legislature.

The Austin-American Statesman, Saturday, July 18, 1903 excerpt courtesy of Newspapers.com. Tile image courtesy of the Internet Archive and Flickr Creative Commons, from the 26th Annual Catalogue and Pricelist of Seeds, 1899 (Alexander Seed Company), U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Library.

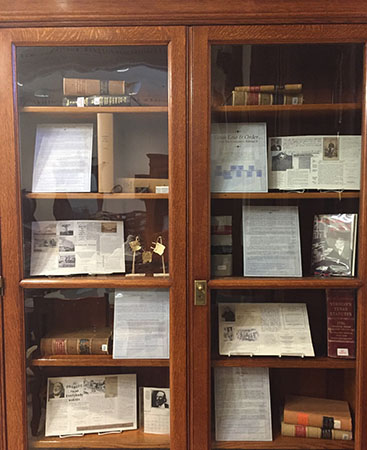

It's easy to take for granted the work of compiling the law. Once the session is over and the governor signs the bills, everything is done, right? Far from it. Preparing volumes that update the law requires time and careful consideration. In this display we took a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the people who laid the foundations for the structure of our laws.

It's easy to take for granted the work of compiling the law. Once the session is over and the governor signs the bills, everything is done, right? Far from it. Preparing volumes that update the law requires time and careful consideration. In this display we took a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the people who laid the foundations for the structure of our laws.Drawing from our "Who Is..." blog series, the exhibit profiles the lives and work of George W. Paschal, John Sayles, H.P.N. Gammel, and Joseph W. Vernon, all of whose contributions we see reflected in our contemporary Texas legislative publications. Learn who hung up the laws to dry after the Capitol fire, who represented the Cherokee Nation in several important cases, who helped establish the law department at Baylor University, and who never resided in Texas but has his name on our law publications today. (And if you can't make it in person, click on the collages below to learn more about Texas' law compilers.)

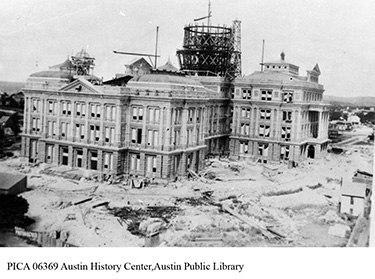

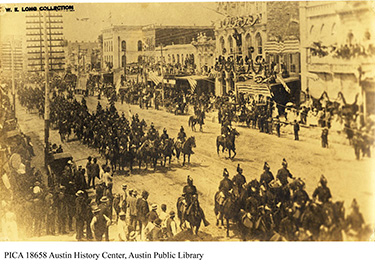

Next week will mark the 130th anniversary since the State of Texas dedicated our current Capitol building. From May 14–19, 1888, more than 20,000 people came from all over the state to participate in festivities such as drill team competitions, military displays, band concerts, and fireworks. The events culminated with the official dedication on May 16, when Sen. Temple Houston (the youngest son of Sam Houston) accepted the building on the state's behalf.

The Constitution of 1876—which is still our constitution today—made financial provision for the new building in Article XVI, Sec. 57, authorizing the use of 3 million acres of public land in the Texas Panhandle to pay for the new capitol and calling on the Legislature to pass the necessary bills to begin the project. (That land would become XIT Ranch.)

In 1879, the 16th Legislature passed SB 21, 16R, "Relating to providing for designating, surveying and sale of three million and fifty thousand acres of the unappropriated public domain for the erection of a new state capitol and other necessary public buildings at the seat of government, and to providing a fund to pay for surveying said lands" and SB 153, 16R, "Relating to providing for building a new state capitol."

To facilitate the passage of Capitol-related bills, several committees were formed. During construction, committees were charged with the "programme" for the laying of the corner stone (1885) and considering the "new Capitol, grounds and cost of furnishing" (1887).

On May 2, 1888, HB 38, 20(1) was approved, "an Act to provide for the reception of the new State Capitol Building." They accepted the Capitol—contingent on the completion of all remaining work—and on May 10, authorized the moving of furniture from the temporary Capitol to the new one. Most offices were established in their new spaces by May 11, and the Legislature convened in its new chambers for the first time.

After the dedication, the work continued: in 1889, committees were formed to investigate the cost of running a capitol elevator, the acoustics of the House chamber, and Capitol grounds considerations like placing "a neat and substantial iron fence around said grounds" and "the cost of properly wiring the Capitol building, with all necessary fixtures, with the view of placing electric lights in said building." Fortunately, they did not use all of the money from the sale of the XIT land to construct the building, so they had some funding left over to address these and other budgetary needs—allocating that money was the reason for the 20th Legislature's special session in April–May 1888.

The work continues today—since 1853, more than 40 committees have been charged with Capitol-related topics. Modernizing the building, repairing after 1983 fire damage, and maintaining the grounds has kept the Legislature (and of course, the State Preservation Board) busy over the years. But, Sen. Houston said it well:

It would seem that here glitters a structure that shall stand as a sentinel of eternity, to gaze upon passing ages, and, surviving, shall mourn as each separate star expires. ~Sen. Temple Houston, Capitol Dedication Speech, May 16, 1888

Images

Top: [Capitol Construction], photograph, 1887~; (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth124107/: accessed May 4, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Bottom: [Cavalry Troops Marching in Texas Capitol Building Dedication Parade], photograph, April 28, 1888; (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth124468/: accessed May 4, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Cover: [Construction of Capitol Dome], photograph, 1888; (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth124243/: accessed May 4, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Sources consulted:

"Capitol," Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association

"Capitol History," Texas State Preservation Board

A Nobler Edifice: The Texas State Capitol, 1888-1988, An Exhibit, the Lorenzo de Zavala State Archives and Library Building. Texas State Library, 1988.

The Texas Capitol: A History of the Lone Star Statehouse. Texas Legislative Council, 2016.

A couple of weeks ago, Texans exercised their right to vote in the primary election. But they probably didn't know that they were voting in a landmark year: 2018 is the 100th anniversary of the first time Texas women were able to vote.

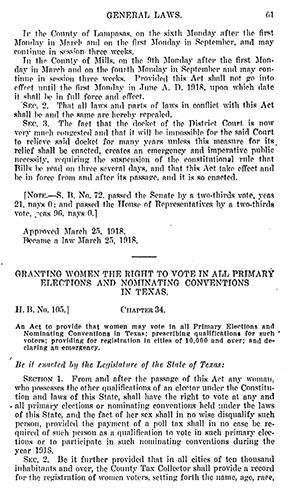

HB 105, 35-4 (1918) was the bill that made it possible, but it was not the Texas Legislature's first effort for women's suffrage. Beginning with the 1868-1869 Texas Constitutional Convention, a resolution was submitted recommending "every person, without distinction of sex" be entitled to vote. However, that provision was amended to read "every male person." In the 1875 Texas "Redeemer" Constitutional Convention, two women's suffrage resolutions were proposed but did not move forward.

In 1893, a statewide women's suffrage convention was held in Dallas, and the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) was chartered. At that point, the 23rd legislative session was almost over, but in the 24th Legislature (1895), Rep. A.C. Tompkins introduced HJR 29 to amend Section 2, Article 6 of the Texas Constitution, allowing all female persons not subject to other disqualification the right of suffrage. The resolution was reported to the Committee on Constitutional Amendments, but was never reported out. TERA ceased functioning in 1895.

In 1903 the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) was formed, and the legislature saw more women's suffrage bills. HJR 17, 30R (1907), by Rep. Jess Baker, was reported favorably out of the Committee on Constitutional Amendments; HJR 8, 32R (1911), also by Baker, received a second reading, and HJR 9, 33R (1913) by Rep. F.H. Burmeister was reported favorably with amendments—but still, women's suffrage bills stalled.

Opposition efforts certainly didn't aid the suffragists' cause: The Texas Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was formed in 1916, and Gov. James Ferguson was vocally against women's suffrage. TESA worked toward the impeachment of Gov. Ferguson through the Women's Committee of Good Government, supported the war effort, and then, in the 4th called session of the 35th Legislature (1918), lobbied Gov. William P. Hobby to include "consideration of the subject of amending the election laws of Texas" among the 172 topics for the special session.

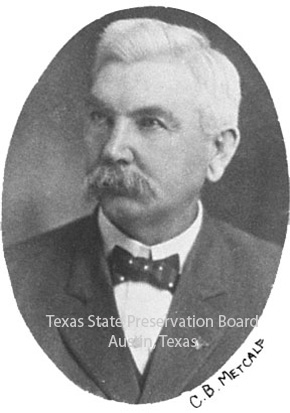

The called session began on February 26, 1918. On March 12, Rep. Charles B. Metcalfe, along with 14 co-authors, introduced HB 105. This bill took an incremental approach: rather than amending the constitution to allow women to vote in all elections, it provided for women to vote in all primary elections and nominating conventions in Texas. The bill passed the House (84-34) on March 15, and passed the Senate (18-4) on March 21.

On March 26, 1918, Gov. Hobby signed HB 105 in the presence of Rep. Metcalfe and other legislators, as well as leaders of the women's suffrage movement, including Minnie Cunningham, Nell Doom, Elizabeth Speer, and Jane McCallum. Rep. Metcalfe provided a fountain pen for the governor and presented it to Cunningham after the signing.

However, the bill did not go into effect for 90 days, and the next primary election was on July 27—this left less than three weeks for women to register to vote. TESA organized to assist women with registering, and more than 386,000 women registered in 17 days.

Of course, the push toward full women's voting rights was not complete. In its regular session, the 36th Legislature passed SJR 7 to amend the Constitution to allow equal suffrage, but the measure was defeated at the polls on May 24, 1919 (with 141,773 votes for and 166,893 votes against).

About a month later, on June 28, 1919, Texas became the ninth state and the first southern state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In the 36th Legislature's second called session, legislators passed HJR 1, "Ratifying an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which provides, in substance, that the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

Visit the LRL to see our "desk" of Rep. Metcalfe as it might have appeared in 1918 when he worked toward the passage of the first women's suffrage bill signed into law in Texas.

Images from top: HB 105, 35-4, as it appears in the session law; Rep. Charles B. Metcalfe, courtesy of the Texas State Preservation Board; Gov. William P. Hobby (seated middle) signing HB 105 in the presence of Rep. Metcalfe (seated to the governor's right) and other legislators, courtesy of a private collection via the West Texas Collection, Angelo State University, San Angelo, TX.

Cover image: San Antonio Express. (San Antonio, Tex.), Vol. 53, No. 86, Ed. 1 Wednesday, March 27, 1918, newspaper, March 27, 1918; San Antonio, Texas. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth434692/m1/1/?q=suffrage: accessed March 15, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Abilene Library Consortium.

Who Is...Gammel?

Jan 17

Every now and then, LRL patrons will ask a question like, "who is Vernon and why is his name on the Texas statutes?" To which we say, "good question!" People often conduct legislative history research with a tight deadline that doesn't leave much time for musing over the origins of the sources, but it can be instructive to learn about who has worked to compile Texas' laws over the years. In our occasional "Who Is…" series, we'll take a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the publishers, lawyers, and legal scholars behind them. Check out our previous entries on Vernon, Sayles, and Paschal; in this post we're focusing on H.P.N. Gammel.

When the old Capitol building burned in 1881, the state lost not only a government building but also its stored copies of session laws and other government records, some dating to the Republic of Texas. Fortunately, a quick-thinking bookseller saw an opportunity for preservation…and a business venture. H.P.N. Gammel’s The Laws of Texas (1822-1897) was the result of his conservation effort and became an essential item in Texas law libraries.[1]

Hans Peter Mareus Neilsen Gammel was born in 1854 in Grenå, Denmark, then immigrated to Chicago in the mid-1870s. At first, Hans was content to stay with his sisters and work to save money to bring his wife, Marie, and baby daughter, Marietta, to Chicago. However, his brother, Nels, had ventured west and had some success in the gold fields. Nels offered to loan the money for Marie and Marietta’s boat fare while Hans accompanied him back west. The brothers made—and lost—money in their ventures together. Rather than returning to Chicago, they decided to go to Texas, attracted by a few Scandinavian settlements near Austin.[2]

Gammel started out in Texas putting up poles and stringing wire for a telegraph company, but he needed a more permanent business when his wife and daughter joined him in Texas at the end of the 1870s. He rented space at Hickory (now 8th Street) and Congress Avenue in Austin, where they could have a storefront with an apartment in the back. He occasionally took contract jobs with telegraph companies, while Marie ran the shop.[3]

The store initially sold writing paper, jewelry, and other general items. One day, however, a man asked to borrow money, offering 24 used books as security. Seeing an opportunity, Hans bargained to buy the books outright for 25 cents. First he read them, helping him begin to understand the public’s reading preferences, and then he bundled them in six-book sets for 25 cents each. And thus, a bookseller’s career began.[4]

Gammel wrote in his diary that his was the “first and only bookstore of any type in this part of the state,” and that he became known as the "10¢ man": “I would buy anything for 5¢ and sell for 10¢. I am sure I sold books worth 5 to 10 dollars for 10 cts., but I am also sure they cost me less.”[5]

Tragedy struck the Gammel family in 1880, when both he and his wife got sick. They sent Marietta to stay with friends, Hans spent six weeks in the hospital, and Marie died. Once Hans regained his health, he sent Marietta to school during the day at the Convent of St. Mary so he could reopen his book stalls. In 1881, he married Josephine Ledel, a Swedish immigrant, at a Pflugerville church.[6]

The couple had been married for just a few months when the Capitol caught fire. At his shop down the street, Gammel witnessed efforts to throw papers and books out the windows to save them, but the combination of fire, rain, and wind had wreaked havoc on the papers, and the building’s superintendent wanted them hauled away. Gammel recalled:

“…I got permission from the authorities to do this job. It meant extra money! That night I lay awake thinking of what I would do with all the rubble. I did not have much knowledge—especially about law books—but the beginning of my love of books had become rooted, and the fact of knowing that all the knowledge and records in those papers would be lost preyed on my mind. I wondered if any of them could be salvaged.

The next morning I put on my hip boots, armed myself with a pick and a shovel, and waded and worked in the slush for days hauling all the rubble—wagonloads of it—to my little house on 8th Street. Mrs. Gammel was not happy about it but she helped me to dry out anything that was not burned to a crisp. We used up all the clothes lines in the yard and strung rope between the trees and on the porches. Then I sorted the papers out the best I could and stacked them in bundles—for why I did not know. I just knew they should not be destroyed.”[7]

Nearly a decade later in 1892, Gammel bought a print shop and established the Gammel Book Company. The press’ first big job was John C. Duval’s Early Times in Texas, and he later printed C.W. Raines’ Bibliography of Texas and Noah Smithwick’s Evolution of a State. Gammel’s primary ambition, however, was to obtain a contract from the House and Senate to print legal documents. His daughter, Dorothy Gammel Bohlender, recalled “It was not by accident that his ‘place of business’ always was near the capitol building. His ‘locality in Austin,’ as he said, gave him a chance to be in touch with events affecting all of Texas, and he wanted to be as close as possible to the men participating in those events.”[8]

Around the same time that Gammel began his printing work, Gov. James S. Hogg appointed C.W. Raines librarian of the Texas State Library. Gammel and Raines developed a mutually beneficial friendship: as a bookseller, Gammel was uniquely equipped to help Raines locate materials for the State Library, and as a printer, he could publish Raines’ scholarly works. On Raines’ part, his legal background and research experience made him a valuable partner to Gammel in putting in order the bundles of papers saved from the Capitol.[9]

In 1898, Gammel published the first of what would be a ten-volume set, The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897. He planned to release one volume every 60 days till completed and set up a system for subscribers to pay as they received volumes.[10] Raines wrote an introduction for it, in which he noted that “these volumes are in the nature of original evidence for the student of our jurisprudence, and that nowhere else can it be so well studied as to its origin, character, successive changes, and its present status as a blended system of the Roman Civil Law and the Common Law of England.”[11]

Gammel’s efforts were widely acclaimed by the Texas legal community. Legal historian Marian Boner attributes some of the success of his publication to the production of two indices that made the texts more accessible, one compiled by George Finlay and D.E. Simmons, and the other by Raines.[12]

With the exception of a brief move to El Paso in the early 1900s, Gammel remained in Austin and in the book business for the rest of his life. He became the state printer in 1901, taking up where his Laws of Texas left off and printing the legislature’s most recent efforts.[13] The bookstore moved occasionally but always was somewhere around Congress Avenue. He died in Austin in 1931 and his son, H.P.N. Gammel Jr., continued the business until his death in 1941.[14] Gammel’s personal book collection had grown in size and substance, and his heirs sold the bulk of it to the notable Texana collector Earl Vandale, who in turn sold his collection to the University of Texas.[15]

When Gammel left Denmark, he had no idea his future lay in legal documents, books, and Texas. The Capitol fire helped to transform him from an everyday bookseller to a preserver and publisher of Texas legal history.

Images from top:

H.P.N. Gammel after he arrived in Austin, taken from H.P.N. Gammel: Texas Bookman, by Dorothy Gammel Bohlender and Frances Tarlton McCallum, Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1985.

Ads for Gammel’s Old Book Store: top, Austin Weekly Statesman, (Austin, Tex.), Vol. 18, No. 21, Ed. 1 Thursday, April 4, 1889. (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth278161/m1/12/?q=gammel: accessed December 7, 2017), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; bottom: St. Edward's Echo (Austin, Tex.), Vol. 5, No. 7, Ed. 1, April 1924. (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth891832/m1/3/?q=gammel%20echo: accessed January 9, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting St. Edward’s University.

Title page from Gammel's. The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897 Volume 1, 1898; Austin, Texas. (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth5872/m1/1/?q=gammel%27s%20laws%20of%20texas: accessed January 9, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu.

Horse-drawn fire wagon on Congress Avenue, photograph circa 1892. “Gammel’s Old Book Store” is on the far right. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth704022/m1/1/?q=gammel: accessed December 7, 2017), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

[1] Dorothy Gammel Bohlender, Handbook of Texas Online, "Gammel, Karl Hans Peter Marius Neilsen," accessed November 27, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fga13.

[2] Dorothy Gammel Bohlender and Frances Tarlton McCallum, H.P.N. Gammel: Texas Bookman, Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1985, pp. 3-6.

[3] Bohlender and McCallum, pp. 7-8.

[4] Ibid., p. 9.

[5] Ibid., pp. 11-12.

[6] Ibid., pp. 15-23.

[7] Ibid., p. 27.

[8] Ibid., p. 43-45.

[9] Ibid., pp. 45-46.

[10] Gammel, Hans Peter Mareus Neilsen, “Compiler’s Notice,” The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897 Volume 1, 1898; Austin, Texas. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth5872/: accessed December 4, 2017), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu.

[11] Raines, C.W., “Introduction,” in Gammel's The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897 Volume 1, 1898; Austin, Texas. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth5872/: accessed December 4, 2017), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu.

[12] Marian Boner, “The Attorney as Author: Books Written and Used by Texas Lawyers,” Centennial History of the Texas Bar, 1882—1982, Austin, TX: The Committee on History and Tradition of the State Bar of Texas, 1981, p. 148.

[13] Boner, p. 148.

[14] "The First Comprehensive Compilation of Texas Law," Jamail Center for Legal Research - Tarlton Law Library, accessed December 4, 2017, http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/gammel-laws-of-texas.

[15] Bohlender and McCallum, pp. 78-79.

Session for the Holidays

Dec 12

Usually, the Texas Legislature is not in session around Christmas time. Since the 16th Legislature (1879), the regular session has begun in January and adjourned in May, generally avoiding winter holidays. (See Article 3141 of the 1879 Revised Statutes of Texas that established this schedule.) However, there were a few instances when sessions started in December and/or continued through the holidays.

In 1847, the 2nd Legislature began work on December 13, 1847, and concluded on March 20, 1848. The representatives and senators worked on Christmas Eve, which fell on a Friday that year. They did take a long weekend and reconvened on Tuesday, December 28.

The 3rd Legislature not only convened on Christmas Eve in 1849 and returned to work on the day after Christmas, they also had a called session in 1850 that ran into the first few days of December.

From the 3rd Legislature through the 8th Legislature, the senators and representatives convened in November and adjourned in February. Typically they met on Christmas Eve, then adjourned until December 26, but they sometimes took a longer break, particularly when the holiday fell on a weekend.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction years, the legislature’s regular sessions were less consistent. The 9th and 10th Legislatures convened in November, but adjourned in January and December, respectively. The 11th Legislature didn’t convene until August 1866, and the 12th Legislature didn’t begin its regular session till January 1871. During these years, if session fell around Christmas, the legislators generally only took Christmas Day off before returning to work.

After an act was passed by the 16th Legislature setting the day and time for session to begin biennially (now Government Code § 301.001), the possibility of session running into the winter holidays was mostly history. However, there are those special sessions! The 71st Legislature had six called sessions, with the second adjourning on December 12; the 72nd Legislature’s fourth called session adjourned on December 3.

These days, Government Code § 662.003 designates December 24-26 as a holiday, but in the days before Texas’ regular session had an officially mandated start time, anything was possible for the legislature! The LRL hopes you enjoy a wonderful holiday season.

Images: top right, House Christmas tree; bottom left: Senate Christmas tree; cover image: detail of House tree.

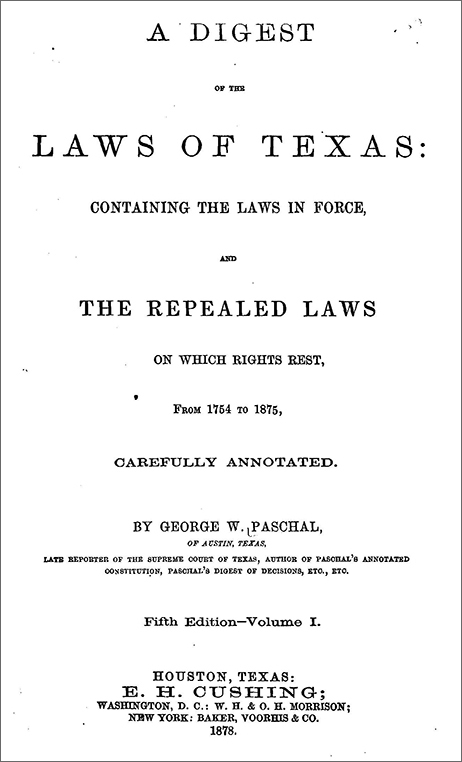

Who Is...Paschal?

Nov 28

Every now and then, LRL patrons will ask a question like, "who is Vernon and why is his name on the Texas statutes?" To which we say, "good question!" People often conduct legislative history research with a tight deadline that doesn't leave much time for musing over the origins of the sources, but it can be instructive to learn about who has worked to compile Texas' laws over the years. In our occasional "Who Is…" series, we'll take a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the publishers, lawyers, and legal scholars behind them. Check out our previous entries on Vernon and Sayles; in this post, we're focusing on George W. Paschal.

From Arkansas Supreme Court justice to newspaper editor, lawyer to court reporter, George W. Paschal wore many hats over his life and never seemed to follow the crowd—in fact, one could argue he relished the path of most resistance. He is responsible for the most successful of the early compilations of Texas statutes, A Digest of the Laws of Texas (commonly referred to as Paschal's Digest).

Born in Skull Shoals in Greene County, Georgia, in 1812, Paschal worked his way through the State Academy in Athens, Ga., by teaching and keeping books.[1] He was admitted to the Georgia Bar before he turned 20 in 1832. He practiced law in Georgia for four years before receiving orders to serve as the aide-de-camp to General John E. Wool with the Georgia Militia, which had been charged with suppressing a Cherokee uprising. Here we get one of our first hints of Paschal's unconventional ways: he married the daughter of one of the Cherokee chiefs, Sarah Ridge. That military campaign led to the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, and ultimately to what we know today as the Trail of Tears.[2]

The couple moved to Arkansas in 1837 to be closer to Sarah's now-relocated family. Paschal began his law practice in Benton County, where he sometimes jointly represented clients with Royal T. Wheeler (future chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court). Sadly, Sarah’s father, brother, and cousin were assassinated in 1839 by Cherokees who were angry about the family’s support of the Treaty of New Echota. The Paschals chose to remain in Arkansas, and in 1843, the Arkansas Legislature selected George as an associate justice on the state’s Supreme Court.[3]

However, he served just one term on the court, then resigned in August 1843 so he could represent the Cherokees in claims against the United States.[4] A victory in that case led to ratification of the Treaty with the Cherokee in 1846, which awarded reparations to the Cherokee.[5]

George and Sarah then moved to Texas around 1846, and George was admitted to the Texas Bar in December 1847. In 1850, Sarah began treating Galvestonians suffering from yellow fever in their home. The couple divorced later that year.[6]

George moved to Austin and remarried (Marcia Duval Price), practiced law, and began work in 1856 as editor of the Southern Intelligencer, an antisecessionist, pro-Union publication. The paper quickly developed a rivalry with the Texas State Gazette, which promoted states’ rights and reopening the slave trade in Texas. The rivalry went as far as a duel challenge, and Paschal resigned his post in 1860.[7] It should be noted that although Paschal was against reopening the slave trade, he also was against abolition and was himself a slave holder.[8]

Paschal further acted on his Unionist principles by representing a captured Confederate conscript, F.H. Coupland, in 1862. He obtained a writ of habeas corpus from his old friend (now Texas Supreme Court Justice) Wheeler, but before it could be served, Coupland was drafted into the army, and Paschal was arrested and jailed for a short time by Confederate authorities.[9]

Indeed, times were tough for a Unionist lawyer in Texas during the Civil War, so Paschal committed himself to preparing the Digest of the Laws of Texas. He writes about this decision in the preface to the Digest’s first edition “…differing as the editor did with the majority of the people of his state, as to the right of secession, and the necessities of the measure, as well as to the possibility of success, and not wishing to seek a professional field elsewhere, had that been possible, he thought that he could not more usefully employ his time than to give those years to the preparation of a book, which should answer the double object of presenting the Statutes, and a pretty full Digest of the decisions of the Supreme Court, in the same volume.”[10]

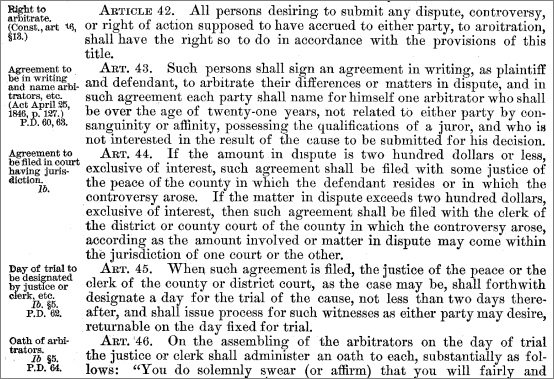

Paschal’s Digest offered a few things not seen in previous legislative publications. Current statutes can trace their history to the sections in his Digest—previously, statutes had been arranged chronologically.[11] Additionally, his statutes presented “the old law, the mischief and the remedy, in the same view”—meaning, he printed the current law alongside the repealed law or judicial changes, using different typefaces to illustrate the development of the law.[12] Finally, and most significantly, “…his digest of laws appeared in five editions, the last one being the basis for the first official compilation of statutes in 1879. Many articles in the [1925] statutes retain not only the substance but also the verbatim phrasing of Paschal’s sections.”[13] (See image of Articles 42-46 from the 1879 Revised Civil Statutes, which includes marginal notes crediting where language was taken from P.D.—Paschal's Digest.)

After the war, Paschal was appointed by provisional governor Andrew Jackson Hamilton as Texas’ agent in a case concerning the Confederacy’s attempts to redeem U.S.-issued bonds to help pay for the Confederate war effort. He ultimately argued before the U.S. Supreme Court and won, helping to provide the definitive ruling on the constitutionality of secession. Paschal also served as counsel in the “Emancipation Cases” to determine on what date enslaved peoples officially gained their freedom in Texas. (The majority ruling settled on the date of ratification of the 13th Amendment.)[14]

In 1868—about the same time that the constitutionally illegitimate Military Court began—Paschal was appointed as court reporter. Drummond observes that “Paschal's reports are characterized by his sometimes polarizing, always frank, and consistently entertaining (and subsequently essential) historical asides contained in the prefaces to each [Texas Reports] volume.” He additionally used the Texas Reports to advertise his other publications. Paschal’s signature candor likely contributed to him losing this job, as he published in Texas Reports his negative commentary on changes to court reporter guidelines.[15]

Paschal then moved to Washington, D.C., where he opened a law office with his sons, George Jr. and Ridge. He also married his third wife, Mary Scoville Harper, and lectured at the Georgetown University law school. He died in Washington in 1878.[16]

In addition to his work with Texas laws, George W. Paschal found himself at the crossroads of many historical events. And as a man dedicated to the law, the defense of them seemed to guide his principles: “Human rights are of all sciences those which most affect human happiness. They can only be preserved by the eternal vigilance of the masses. That vigilance should constantly be directed to our laws, organic or statute. It is under the forms of these that liberty is preserved or lost.”[17]

Photograph of George W. Paschal courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Title page of Paschal's Digest taken from the LRL's digitized 5th edition. Excerpt of Title VI, Articles 42-46 from the 1879 Revised Civil Statutes, courtesy of the Texas State Law Library's Historical Texas Statutes digital collection.

[1] Amelia W. Williams, "Paschal, George Washington," Handbook of Texas Online, accessed August 29, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpa46.

[2] Dylan O. Drummond, "George W. Paschal: Justice, Court Reporter, and Iconoclast," Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society 2:4 (Summer 2013), accessed 2017 October 17, http://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/george-w-paschal-justice-court-report-22105/, p. 7.

[3] Drummond, p. 8.

[4] Drummond, p. 8.

[5] Treaty with the Cherokee, 9 Stat. 871, 874 (1846)

[6] Drummond, p. 8.

[7] Williams; Drummond, p.8.

[8] Williams; Kevin Ladd, “Pix, Sarah Ridge,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 15, 2017, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpi30; Fannie E. Rachford, “O’Connor, Elizabeth Paschal,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed November 15, 2017, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/foc12.

[9] Drummond, p. 8.

[10] "Preface [to the first edition, 1866], " A Digest of the Laws of Texas, 5th edition, edited by George W. Paschal. Houston, TX: E.H. Cushing, 1878, p. iv, http://www.lrl.texas.gov/collections/Paschal.cfm.

[11] "Legislation," rev. by Linda Gardner, A Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History, edited by Karl T. Gruben and James E. Hambleton, Austin, TX: Butterworth Legal Publishers, 1987, pp. 16-17.

[12] "Preface [to the first edition, 1866], " p. iv.

[13] Marian Boner, "The Attorney as Author: Books Written and Used by Texas Lawyers, " Centennial History of the Texas Bar, 1882—1982. Austin, TX: The Committee on History and Tradition of the State Bar of Texas, 1981, p. 145.

[14] Drummond, pp. 9-10.

[15] Drummond, p. 11.

[16] Williams.

[17] "Preface to the fourth edition [1874], " A Digest of the Laws of Texas, 5th edition, edited by George W. Paschal. Houston, TX: E.H. Cushing, 1878, pp. xi-xii, http://www.lrl.texas.gov/collections/Paschal.cfm.

Who Is...John Sayles?

Oct 31

Every now and then, LRL patrons will ask a question like, "who is Vernon and why is his name on the Texas statutes?" To which we say, "good question!" People often conduct legislative history research with a tight deadline that doesn't leave much time for musing over the origins of the sources, but it can be instructive to learn about who has worked to compile Texas' laws over the years. In our occasional "Who Is…" series, we'll take a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the publishers, lawyers, and legal scholars behind them. Check out our previous entry on Vernon; in this post, we're focusing on John Sayles.

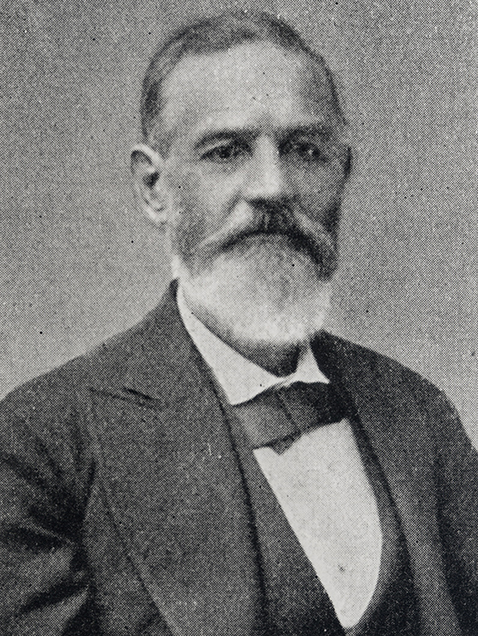

John Sayles was a prolific legal mind for Texas, producing more than 15 works on Texas law. Most notably, he prepared what can be considered the last important unofficial compilation of Texas laws, Sayles' Early Laws of Texas. Additionally, the state's first set of annotated statutes were edited by John and his son, Henry, in 1888.[1] Father and son kept these statutes and annotations up to date until the 1911 revision, when the Vernon Law Book Company bought the copyright.

Born in Ithaca, New York, in 1825, Sayles taught in various schools as a young man to finance his education. He earned his bachelor of arts degree from Hamilton College in New York in 1845, then moved to Texas, seeking opportunity in the country's newest state. He taught school in Brenham, read law, and was admitted to the Texas Bar in 1846. He purchased a plantation and in 1849, married Mary Elizabeth Gillespie. They went on to have six children.[2] According to the U.S. Eighth Census in 1860, Sayles was reported as holding 44 enslaved people, $15,000 in real property, and $61,000 in personal property[3]—which, taking inflation into account, would have made him a millionaire by today's standards.

From 1855-1856, Sayles represented Washington County in the House of Representatives of the 6th Legislature.[4] Historian Ralph A. Wooster identified Sayles as a member of the Texas Know-Nothing party.[5] Following Sayles' term in the legislature, he taught at Baylor University in its newly formed law department from 1857-1860. He also started his publishing work, with such titles as A Treatise on the Practice of the District and Supreme Courts of the State of Texas (1858), which the Handbook of Texas describes as a "forerunner of special studies on probate law, justice of the peace jurisdiction, business transactions, and Masonic jurisprudence."[6]

Baylor's law department became inactive when many male students and faculty, including Sayles, left to join Confederate troops in the Civil War. He served in the 4th Infantry Regiment as a Colonel, then attained the rank of Brigadier General and served with Brigade No. 23.

When the war was over, Sayles resumed his legal practice and teaching at Baylor. He also continued to compile and publish Texas law, including various editions of the Texas Constitution. The HathiTrust makes available digital versions of many of his works.

Users of Sayles' texts, then and now, note that he does not discuss all of the Early Laws of Texas—he omits many statutes. His interest seems to fall primarily in the land and colonization laws of Spain and Mexico, and so the publication is most useful for land-title research. Among other information, Sayles provides a glossary of terms used in the old surveys and land grants and a table of land measures, which can be very helpful to researchers unfamiliar with the jargon of the day and industry.[7]

John moved to Abilene around 1886 with his son, Henry, where they practiced as Sayles & Sayles and collaborated on legal publications. John died in 1897, but Henry continued the work of updating the annotated statutes until the Vernon company bought the copyright and took over the publication.[8]

Photograph of John Sayles courtesy of the Texas Jurists Collection, 1936-1992, Tarlton Law Library, Jamail Center for Legal Research. Photo of Sayles volumes at the Legislative Reference Library courtesy of LRL staff.

[1] "Legislation," rev. by Linda Gardner, A Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History, edited by Karl T. Gruben and James E. Hambleton, Austin, TX: Butterworth Legal Publishers, 1987, pp. 16-17.

[2] Handbook of Texas Online, "Sayles, John," accessed August 29, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fsa42.

[3] Ralph A. Wooster, "An Analysis of the Texas Know Nothings," The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 70, July 1966-April 1967, Texas State Historical Association. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth101199/: accessed August 29, 2017), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Texas State Historical Association, p. 446.

[4] "John Sayles," Texas Legislators: Past & Present, Legislative Reference Library of Texas, accessed August 29, 2017, http://www.lrl.texas.gov/legeLeaders/members/memberDisplay.cfm?memberID=5202.

[5] Wooster, p. 416.

[6] Handbook of Texas Online.

[7] "Legislation," p. 16

[8] Handbook of Texas Online.

Capitol Spirits: Bats!

Oct 24

For the past few years around Halloween, we've shared ghostly stories relating to Texas—see last year's post and our "Capitol Spirits" Pinterest board. This year, we thought we'd do something a little different and write about one of Texas' official state symbols that is commonly associated with Halloween: bats.

After all, Texas' official flying mammal is the Mexican free-tailed bat, per SCR 95, 74R. Did you know that Texas is home to the world's largest known bat colony, in Bracken Cave Preserve in Comal County? Bracken Cave is host to more than 15 million Mexican free-tailed bats, making it one of the largest concentrations of mammals on Earth. Texas also boasts the world's largest urban bat colony, with about 1.5 million Mexican free-tailed bats residing under the Ann W. Richards Congress Avenue Bridge in Austin, right down the street from the Texas Capitol.

These bats live in Texas from around March through late October, then migrate to warmer southern climes in Mexico. Both the bridge and Bracken Cave are maternity colonies, meaning that millions of baby bats are born in these locations each summer, too.

Some people are concerned about bats, with practical worries about rabies and guano and/or fears of the supernatural connotations of the creature. However, Bat Conservation International (headquartered in Austin) works to educate the public that bats are safe as long as people don't try to handle them, guano is good fertilizer, and bats offer excellent natural pest control services! A nursing mother bat consumes up to her body weight in insects each night. It's been estimated that all together, the Bracken Cave bats eat 250 tons of insects, and that the Austin bats eat five to ten tons of insects.

However, Bracken Cave and Austin are not the only places bats live in Texas, and our state is home to 32 of the 47 species of bats found in the United States. For information about where to go to view a bat emergence (when they come out to hunt insects at dusk), visit the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department's Bat-Watching Sites of Texas guide.

In addition to bats, there are a couple of other Texas state symbols associated with Halloween. The pumpkin was declared the official state squash in 2013 (HCR 87, 83R), with Texas being the fourth leading state in commercial pumpkin production. And while the official rodeo drill team (HCR 136, 80R) is distinctly of this plane, the Ghostriders' eerie name evokes the story of a cattle drive gone awry that inspired ghost stories and the famous song, "Ghost Riders in the Sky."

Sources:

"Bat-Watching Sites of Texas," Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/species/bats/bat-watching-sites/, accessed 2017 September 29.

"Bracken Cave: Protecting a Jewel in Texas," Bat Conservation International, http://www.batcon.org/our-work/regions/usa-canada/protect-mega-populations/bracken-cave, accessed 2017 September 29.

"Protect Mega-Populations: Congress Avenue Bridge," Bat Conservation International, http://www.batcon.org/our-work/regions/usa-canada/protect-mega-populations/cab-intro, accessed 2017 September 29.

Images:

Top right: Bats emerging from the Bracken Cave, photo by Flickr user U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters.

Bottom left: People watch the bat emergence from the Ann W. Richards Congress Avenue Bridge and from boats on Lady Bird Lake in Austin, photo by Flickr user Woody Hibbard.

Who Is…Vernon?

Sep 27

Every now and then, LRL patrons will ask, "who is Vernon and why is his name on the Texas statutes?" To which we say, "good question!" People often conduct legislative history research with a tight deadline that doesn't leave much time for musing over the origins of the sources, but it can be instructive to learn about who has worked to compile Texas' laws over the years. In our occasional "Who Is…" series, we'll take a look at some of the important resources for studying Texas legislative history and the publishers, lawyers, and legal scholars behind them.

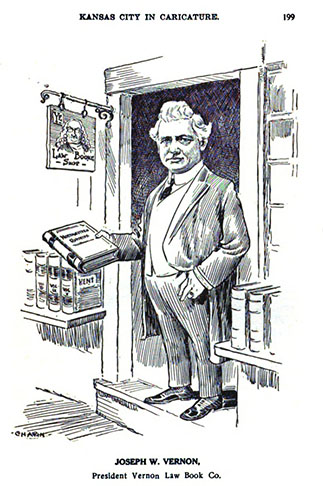

Many of the people we've come to associate with Texas law book publications were Texans or resided in Texas at some point. Despite having his name on the statutes we use today, Joseph W. Vernon is not one of them. Born in Wisconsin in 1860, Vernon graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1885 and moved to Kansas City, Missouri in 1886. In September 1902, Vernon organized the Vernon Law Book Company.[1]

Texas' first set of annotated statutes were published by John and Henry Sayles in 1888. (More on the Sayles in a future post.) Before their 1911 revision, the copyright was bought by Vernon, and in 1914, an edition called Vernon's Sayles was produced. The Sayles name was dropped with the 1925 edition, which was the last official edition of the Texas statutes.[2] Vernon was noted as an active member of the Kansas City community before he died in 1928 at the age of 68.[3]

Vernon Law Book Company published an unannotated Centennial Edition in 1936, and another unannotated compilation in 1948.[4] In 1969, West Publishing took over the company and its operations, and Vernon's compilations were certified by the Texas Secretary of State.[5] Despite changes in publisher (which is now Thomson Reuters), the statutes volumes are still familiarly known as Vernon's, or as the Black Statutes (so called because of their black binding).

Vernon's Texas Statutes and Codes Annotated are a critical first stop when conducting legislative history research. Annotations provide background on revisions to sections of code, references to law reviews, attorney general opinions, and more.

In the course of legal research, you may also come across the "Red Statutes," unannotated biennial supplements which were published from 1948 through 1974, with a supplement for each legislature; and their successors, the "Green Statutes," also unannotated statutes that were produced in two forms: hardback and paperbacks filed in a binder.

You can see the current statute publication dates for each bound volume of Vernon's Statutes here. In 1963, the Texas Legislature passed legislation requiring the Texas Legislative Council to make a complete, non-substantive revision of Texas statutes. When the program is complete, all general and permanent statutes will be included in one of 27 codes. Look on our statutory revision page to see a list of these codes, along with links to statutory revision documents.

[1] Lydia M.V. Brandt, Texas Legal Research: An Essential Lawyering Skill, Dallas, TX: Texas Lawyer Press, 1995, p. 348.

[2] "Legislation," rev. by Linda Gardner, A Reference Guide to Texas Law and Legal History, edited by Karl T. Gruben and James E. Hambleton, Austin, TX: Butterworth Legal Publishers, 1987, pp. 17-18.

[3] Brandt, p. 348.

[4] Gardner, p. 18.

[5] Paris Permenter and Susan Fischer Ratliff, Guide to Texas Legislative History, Austin, TX: Legislative Reference Library, 1986, p. 11.

[6] Gardner, p. 18.

Photograph of Joseph Whiteford Vernon courtesy of findagrave.com. Drawing of Vernon can be found in Kansas City in Caricature, digitized by HathiTrust. Cover image of the 1948 Vernon's Texas Statutes courtesy of the Texas State Law Library's Historical Texas Statutes digital collection.